A Singer’s Life: Preparation Pt1

Earlier in A Singer’s Life, I wrote about the actual process of rehearsing an opera, from the first rehearsal to the opening night. This was one of the most commented on of the articles I have written over the past year, presumably because no one had ever explained to our audience how we get to the point of performance. You, the audience, are only allowed to see the final result, often of weeks and even months of work. The whole process of rehearsal, both with stage director and musical director, has been something of a mystery. It has occurred to me, however, that I had inadvertently omitted a complete stage of the process – how we arrive at that first rehearsal, when we meet our colleagues in the cast, and find out what ideas are to come over the next few weeks of rehearsal.

I explained that we arrive at that first meeting, having learned the notes and the words, and committed them to memory, but neglected to explain how we do this. Now, all singers have their own methods of preparation, and I wouldn’t attempt to speak for my colleagues, but I thought it might be of interest to find out how I do it.

Let’s go to the very first moment of any new opera production. There are two basic methods of finding yourself in an opera. Either the management or your agent rings up, or nowadays sends an email, and says: “There is to be a production of So and So’s opera, “Such and Such”, somewhere, sometime. Are you free and interested to sing the role of Blah?” This is very rare! Normally, the management or your agent rings up and says: “There is going to be a production of “Such and Such”. They are interested in you singing Blah, so can you get to somewhere for the audition?” This is not rare.

Let’s go with version 2, as we are in the real world. Let’s also go with the agent bit too, not the management, as that is largely the reality! Before we proceed, I think it is essential to write about agents. There has been a series recently on TV, on one of the subscription channels, from France, called ‘Dix Pour Cent’ (Call my Agent, in English). This is a very funny look at the world of an artists’ agency in Paris, primarily for film and stage actors, and the machinations involved in casting, and juggling dates and actors. Ten per cent (dix pour cent) seems to be the typical agent’s cut in this world. Obviously, all the characters are hugely exaggerated (although many of the agency’s clients are real film stars playing heightened versions of themselves), and this gives the show its comic value.

The reality of singers’ agents is much more mundane, but actually crucial to our careers. I have been involved recently in helping young singers to climb on to the career ladder (I was, for 10 years Honorary Professor of Singing at St Andrews University), and it is very clear that, perhaps even more than in my youth, having an agent is critical in the search for work. As in all walks of life, luck and knowing the right people are as important as raw talent. It was the case back in the late 70s as it is now, that everyone needs some sort of spark to set a career alight. The talent should take you so far, perhaps a place at a music college, or a role in some show that suddenly attracts media attention. However, to move on to the next stage, it is usually the winning of a competition, or an appearance at an event which people in management are aware of and which stands out, that results in the advancement of a career.

In my case, having got on the singers’ course at the Guildhall School of Music in London, we were lucky that the major broadsheet newspapers covered the student opera productions there. Consequently, my name became known to a few interested parties, and some good write-ups brought me more attention. I spent a couple of summers at the Britten-Pears School at Snape near Aldeburgh, and more influential people heard and liked my singing. In the winter of 79/80, I was invited to audition for some masterclasses to be given at the Edinburgh Festival in August 1980 by Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, an enormously famous soprano. After a general audition, I went to Peter Pears’ flat in Islington, where I met Madame Schwarzkopf, and the director of the Edinburgh Festival, John Drummond. Consequently, that summer I appeared with five other young singers, and the distinguished accompanist, Roger Vignoles (who I knew from Aldeburgh), on the stage of the Freemasons’ Hall in Edinburgh’s New Town, before an enthusiastic audience and the BBC cameras. My lesson on Leporello’s Catalogue Aria from Mozart’s ‘Don Giovanni’ proved a particularly successful segment when broadcast the following year (you can find it on YouTube below – swoon at the tall, manly bloke with the black beard and the lovely voice!), and I was suddenly sort of famous.

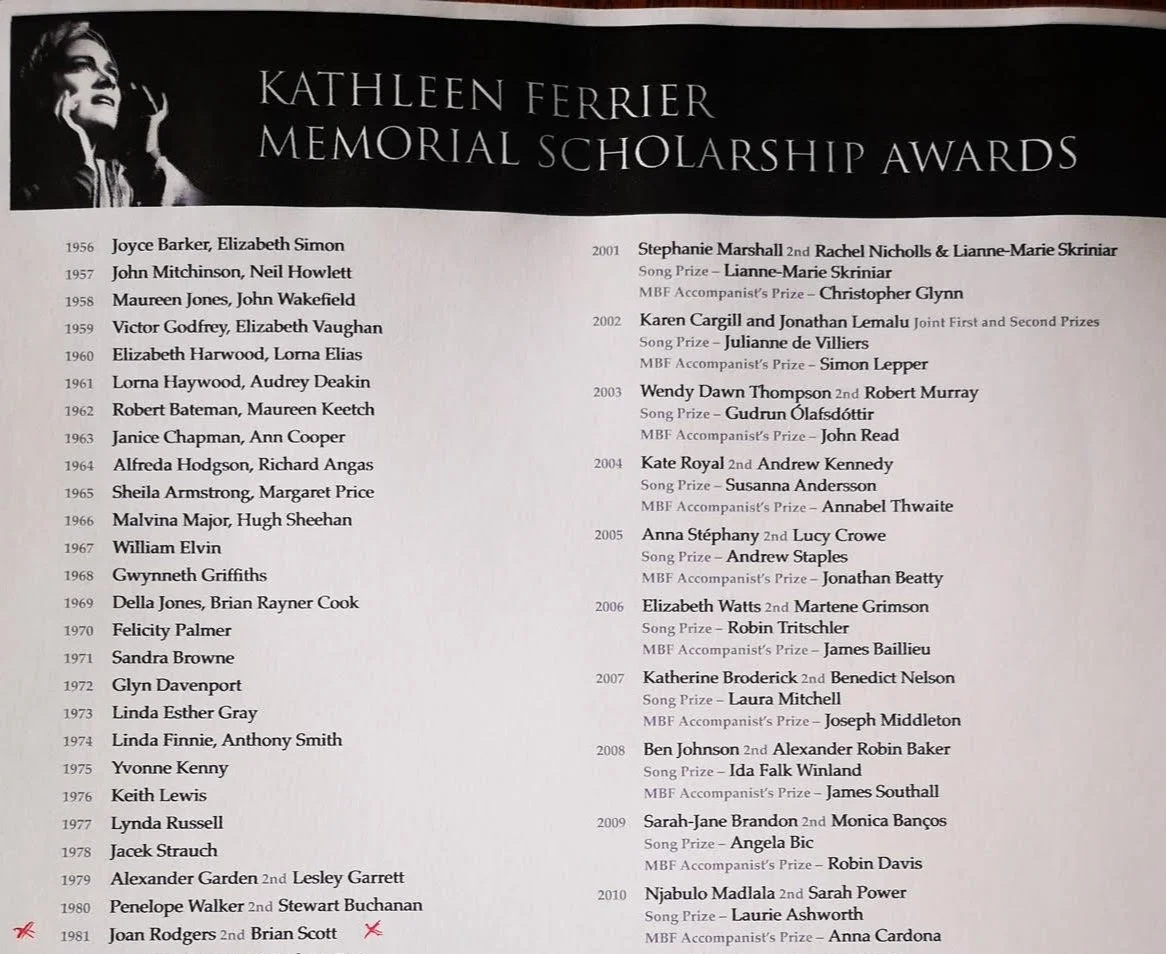

That year of 1981, I also won the Decca Kathleen Ferrier Prize, one of two prizes awarded each year after various rounds of the competition in the Wigmore Hall in London.

These two events resulted in me obtaining my first agent, Basil Douglas, and I was taken on by one of his team, a young graduate of St Andrews whom I knew vaguely. Instantly, I got a contract to sing that autumn at the Teatro la Fenice in Venice, and in Rome the following year, and by summer 1982 I had a contract at Scottish Opera as a company solo bass. Without an agent, I would certainly not have got any of these contracts! Over the many years since then, I have had a handful of agents, only moving on if I felt that I was slipping down the pecking order of their lists. For the last 20 years, I have been with Robert Gilder and Company, a contemporary of mine, who has been responsible for many of my wonderful contracts in the latter part of my career. It is a marvellous feeling to know that someone else is out there fighting for you and dealing with the money side of things. The financial aspect is perhaps the most important side to an agent’s work. We singers have literally no idea what we are worth, and we never talk to each other about money. In all my 40 years plus as a professional singer, I have never had the slightest idea what any of my colleagues were earning, nor any wish to know. Provided we trust our agents, we can safely leave the money side to them, safe in the knowledge that the more I earn, the more he earns, typically a cut of 10% to 15%, depending on the contract or the country involved. Over the last 25 years, I have also used a concert agency, presently Ann Ferrier Artists. Robert Gilder has never been particularly interested in concert work for his artists, so he is happy for me to be represented by Ann for concerts (do get in touch with her if you need a thrilling bass!).

So, returning to the original thread of this article, the artist is contacted by his/her agent about an audition for a particular role. As I have matured as an artist, the sorts of auditions I am interested in have changed. When I was young and relatively unknown, it was all about putting yourself out there in the marketplace, and I would often find myself in general auditions for large companies, taking place over several days. Truth be told, I rarely got any work out of these auditions, and often spent stupid sums of money chasing work that was a chimera. I remember a couple of weeks driving round Germany, with my father for company, becoming more and more frustrated by the idiotic auditions I had been sent to. I would turn up at some town, deep in the Black Forest perhaps, to find that they were looking for a high baritone, or a tenor. Nobody cared. I had been sent out by an agency in Vienna, who knew next to nothing about me, on the off chance that I might get a two year contract in ‘Dickelheim im Wald’, or somewhere, that would earn them a decent amount of money. What I spent on all this was completely immaterial to them. Fortunately, the Bank of Mum and Dad was there to help, and actually that trip was a most fabulous experience for both me and my Dad, in which we bonded in a wonderful way, through adversity. It wasn’t all bad. We saw great places and ate and drank splendid German food, wine and beer, but I got zero work.

The other thing that I discovered over those early years was never to trust your own impressions of an audition. The number of times I have come out and moaned to Fran about the useless audition, only to find I had been successful, is huge. The opposite is also true! For the last 20 years or so, I have refused to go to any general auditions. I will go to sing to someone for a specific role in a specific place. End of story. However, I am old enough and experienced enough and, dare I say it, well-enough known, that I refuse to flog along to some audition, just to satisfy someone’s ego. Indeed, most of my work over the past two decades has come directly through my agent talking to management on my behalf and dispensing with the whole audition thing altogether. I am actually surprised how much work still has to be auditioned for, but I suppose one has to be seen as being fair and objective.

Let’s assume that the singer has been selected for a certain role in a certain opera, to commence rehearsals at a certain date for an opening night on a certain date sometime later. As a singer, we need to know what that role is like, what language it is in, and what amount of time is needed to learn it and memorise it. Therefore, before we sign any contract, we have to be aware of any pitfalls, either musically or logistical, which would prevent us from singing it well and making a success of it, both for ourselves but also for the company. This is because, for every contract, we hope it will lead to a second contract, and then a third and so forth. It doesn’t always work out like that, but you have to hope that this contract is the start of a beautiful relationship with that particular company. You also have, of course, to be prepared for that relationship to change, and maybe sour a bit, as casting directors move on, or managements change completely. It is a notoriously precarious business, and you have to be sanguine about the possibility of going out of favour eventually, often through no fault of your own. Like all of us, casting directors are subjective, and we must always be ready to be rejected, only to rise again, phoenix-like, somewhere else. I have been enormously lucky, over these 40 plus years, to be almost always in work, with very few long breaks. I was also extremely lucky to be married to a wonderful woman, who, as well as putting up with me being away more than half the year, was also able to hold down a very well-paid salaried job as an accountant. Fran and I recently celebrated our 42nd anniversary, and, to quote the old song - “It don’t seem a day too much!”

In the second part of this article about preparation, I’ll attempt to explain how we go about the actual process of learning and preparing a role, and maybe give the odd hint or tip to young, emerging singers as I go along.